“

The human brain is divided into several lobes, each responsible for essential mental and bodily functions. Understanding the functions of different brain lobes provides insight into how we think, move, feel, and remember. These brain regions—frontal, parietal, temporal, and occipital—work in unison yet specialize in distinct areas of cognition and behavior. 1

1

”

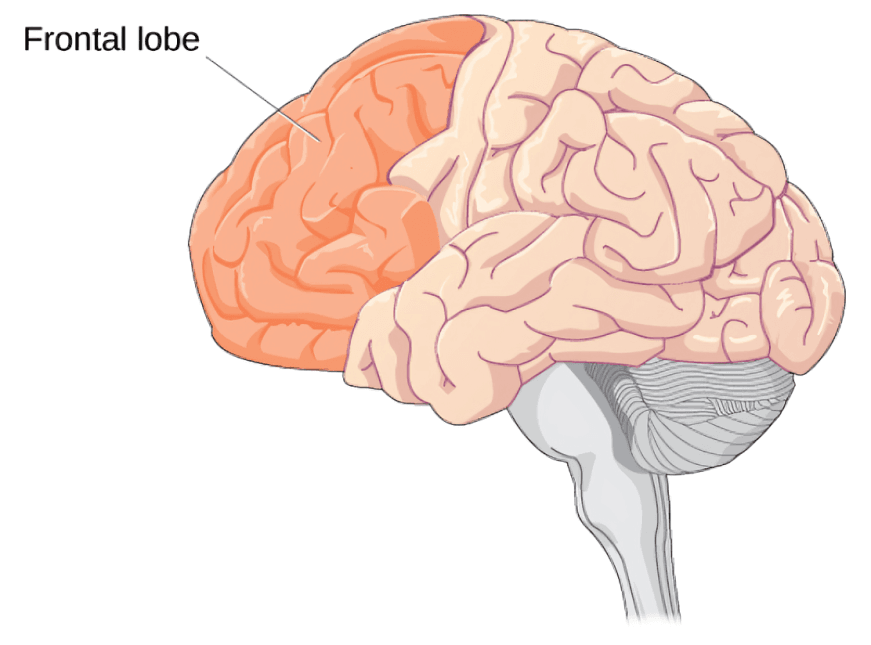

The frontal lobe is the brain’s control center for decision-making, reasoning, and personality. It enables logical thinking, self-awareness, and planning by integrating emotional and cognitive inputs. 1

Located behind the forehead, the frontal lobe also manages voluntary muscle movements. It coordinates movement, speech, and expressions by signaling the motor cortex. 2

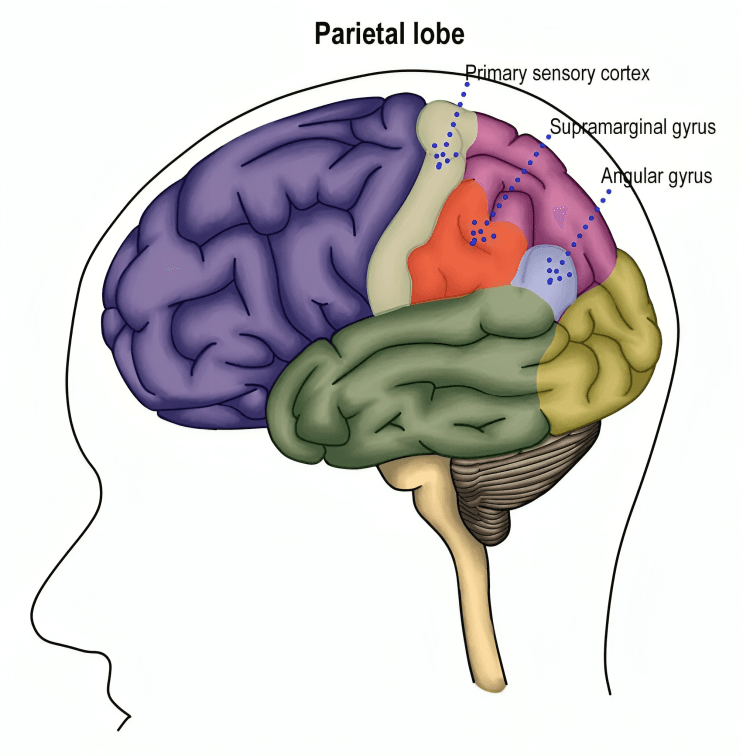

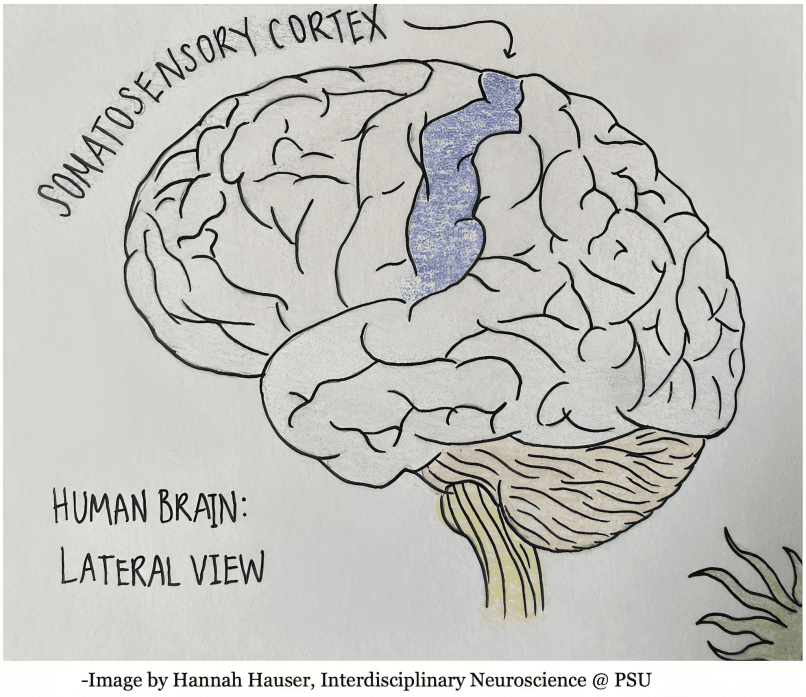

The parietal lobe interprets sensory data like touch, pressure, pain, and temperature. It allows you to feel textures, recognize spatial orientation, and perform arithmetic tasks through detailed neural processing.

Damage to the left parietal lobe can cause difficulty with reading, writing, and math. This highlights its key function in understanding symbols, language structure, and logical number patterns in daily activities. 3

The temporal lobe plays a critical role in memory formation and auditory processing. It helps identify sounds, comprehend speech, and encode long-term memories, especially in the hippocampus. 4

The temporal lobe is also involved in emotion regulation. Its close connection with the limbic system supports emotional memories, making it essential for empathy, fear responses, and social interactions. 5

The occipital lobe, located at the back of the brain, is primarily responsible for visual processing. It interprets color, motion, shapes, and depth, transforming retinal data into clear visual perception. 6

The frontal lobe also supports working memory and abstract thought. When solving puzzles or moral dilemmas, this lobe analyzes, prioritizes, and judges outcomes at once. 7

When we interpret facial expressions or tone of voice, the temporal lobe activates to match emotional cues with memory and meaning—key in understanding sarcasm, empathy, or someone’s mood. 8

The somatosensory cortex within the parietal lobe creates a "map" of your body. It registers sensations from different areas, enabling accurate responses to stimuli like heat, vibration, or gentle pressure.

Reading Braille activates the occipital lobe in blind individuals. This adaptation shows the brain’s ability to repurpose lobes across senses, allowing visual areas to process tactile information instead. 9

The prefrontal cortex, part of the frontal lobe, controls impulse regulation and social behavior. It helps you pause before acting, consider others’ feelings, and make ethical decisions with foresight. 10

Temporal lobe epilepsy can affect memory and emotional balance. Seizures in this region may trigger déjà vu, intense emotions, or hallucinations, showing how tightly this lobe is linked to consciousness. 11

Multitasking engages several lobes simultaneously. The frontal lobe manages switching between tasks, the parietal lobe tracks input, and the temporal lobe retrieves relevant information based on context. 12

Damage to the occipital lobe doesn’t just affect eyesight—it can distort visual memory and dream imagery, showing how sight and imagination share pathways in the brain’s visual processing center. 13

The frontal lobe continues developing into early adulthood, explaining why teenagers often show impulsive behavior and struggle with planning. Maturation brings improved focus, judgment, and self-control.

Visual illusions trick the occipital lobe, revealing its reliance on context. What you "see" is often a result of brain assumptions, not just direct image translation from the eyes. 14

Body schema disruptions, like neglecting a limb after stroke, stem from parietal lobe damage. Patients may deny ownership of a body part, showing how brain maps construct physical self-awareness. 15

The angular gyrus, located between the parietal and temporal lobes, helps link visual input with language and numbers. It’s crucial in reading, understanding metaphors, and solving arithmetic problems. 16

Philosopher René Descartes studied brain anatomy to understand thought and existence. His work sparked exploration into brain lobe functions, merging philosophy with neuroscience. 17