“

Understanding Seasonal Affective Disorder (SAD) reveals how seasonal changes affect emotional well-being. Often triggered by reduced sunlight during fall and winter, this condition impacts energy, sleep, and mood patterns. Understanding Seasonal Affective Disorder (SAD) helps identify symptoms, seek support, and explore beneficial treatments like light therapy, lifestyle changes, and counseling.1

1

”

SAD is recognized as a subtype of major depressive disorder, characterized by a recurring seasonal pattern. Symptoms often begin in late fall or early winter and remit during the spring and summer months. 1

The prevalence of SAD varies geographically, with higher rates observed in regions farther from the equator. This distribution is attributed to reduced sunlight exposure during the winter months in higher latitudes. 2

Common symptoms of SAD include persistent low mood, loss of interest in activities, fatigue, and changes in sleep and appetite patterns. These symptoms can interfere with daily functioning and quality of life. 3

Winter-pattern SAD often presents with hypersomnia (excessive sleeping), increased appetite, weight gain, and carbohydrate cravings, distinguishing it from other forms of depression. 4

Light therapy, involving exposure to bright artificial light, is a first-line treatment for SAD. It aims to compensate for the lack of natural sunlight and can alleviate depressive symptoms.

Summer-pattern SAD, though less common, can occur and is characterized by symptoms such as insomnia, decreased appetite, weight loss, and heightened anxiety. 5

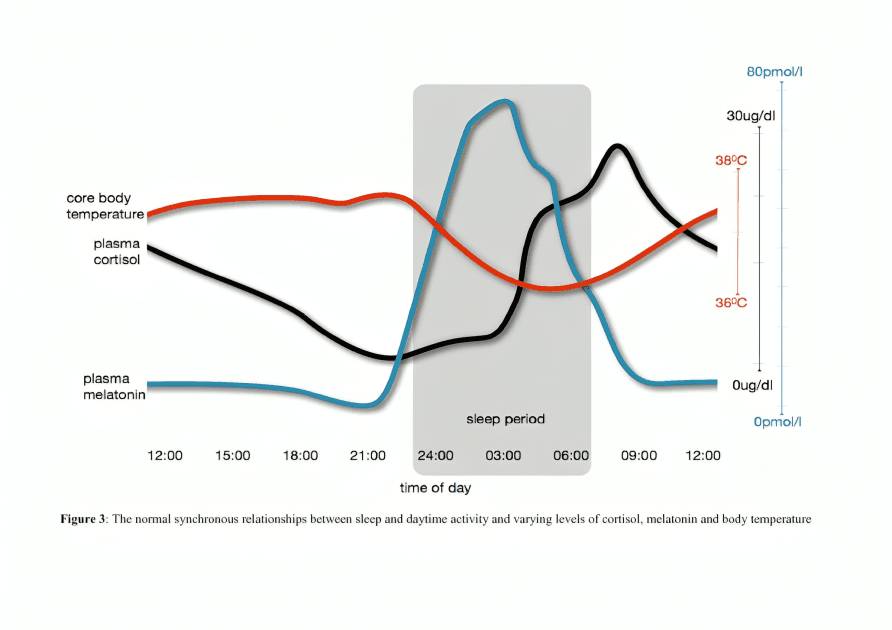

The exact cause of SAD is not fully understood, but it is believed to be related to changes in circadian rhythms, serotonin levels, and melatonin production due to seasonal variations in light exposure. 6

Cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) has been adapted for SAD and focuses on identifying and modifying negative thought patterns and behaviors associated with the disorder. 7

Antidepressant medications, particularly selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), may be prescribed for individuals with severe SAD symptoms or those who do not respond to light therapy. 8

Vitamin D supplementation is sometimes recommended, as low levels of vitamin D have been associated with depressive symptoms, although evidence on its efficacy for SAD is mixed. 9

Spending more time outdoors during daylight hours, even on cloudy days, can significantly increase light exposure and improve symptoms of SAD by aligning natural circadian rhythms with environmental cues.

Social support and consistent engagement in enjoyable activities are especially important for individuals struggling with SAD, as emotional isolation can greatly exacerbate depressive symptoms. 10

Younger adults are significantly more likely to experience SAD, and the risk typically decreases with age. This trend may relate to lifestyle shifts and biological changes across different life stages. 11

Individuals who have a family history of depression or SAD may possess an increased genetic vulnerability, suggesting a strong potential hereditary component that affects how their brain processes seasonal light changes. 12

Dawn simulators, which gradually increase indoor light levels in the bedroom each morning, can serve as a beneficial alternative to traditional light therapy for individuals with SAD. 13

Chronotherapy, which adjusts sleep-wake cycles, is a promising treatment for SAD. It helps reset disrupted circadian rhythms that can negatively affect mood during the darker seasons.

Some individuals diagnosed with SAD may benefit from carefully timed melatonin supplements taken in the late afternoon or evening. However, timing and dosage should always be guided by a licensed physician. 14

Philosopher Aristotle once noted how "the soul suffers when deprived of light," echoing how SAD disrupts mental harmony. SAD treatments today aim to restore balance using both modern science and light-based therapies. 15

Dr. Norman E. Rosenthal, the psychiatrist who first identified and named SAD in the 1980s, emphasized the importance of recognizing its seasonal nature early to ensure timely intervention. 16

Ongoing research continues to explore the biological mechanisms underlying SAD, including the role of neurotransmitters, circadian rhythms, and genetic factors, to develop more effective treatments. 17